Lucas Dragone has traveled around the world to capture iconic and significant instances of human performance across disciplines, traditions, and continents. This work often involves meeting and videoing artists and theatrical practitioners that have dedicated their lives to their craft. Most recently, Lucas has traveled throughout Japan meeting, learning from, and recording masters in the arts of Butoh, Bunraku, and Kagura.

Butoh

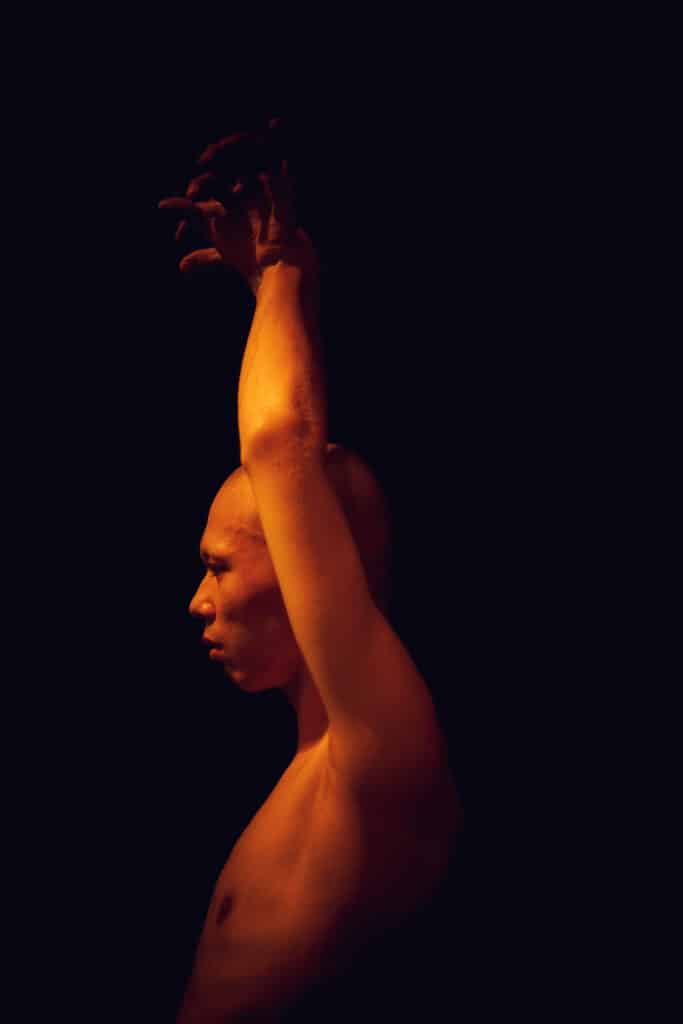

The journey began with a short trip to visit two Butoh masters an hour outside of Tokyo. Butoh Masters Kayo Mikami and Yukio Mikami (Yukio Mikami is pictured above and below) invited Lucas to their space, a small black box behind a house, where they conducted a workshop with an ensemble of dancers. Their company is called Torifune Butoh Company. Many of the performers were at middle age or older, a characteristic not uncommon in Butoh dancers.

The 4-hour workshop, broken into two 2-hour sections, was spent mostly working with the dancers onstage, in the space. Lucas excitedly explained that just like Franco’s process, it made the actors work naturally in the space.

In this experience, the Butoh masters and dancers emphasized energy and intensity. Throughout the workshop, the masters would often work with the dancers on simply being present and focused. Lucas pointed out that the most difficult moments, requiring the most experienced performers occurred when the performer was doing the least onstage. This too seemed familiar and in line with European performance tradition.

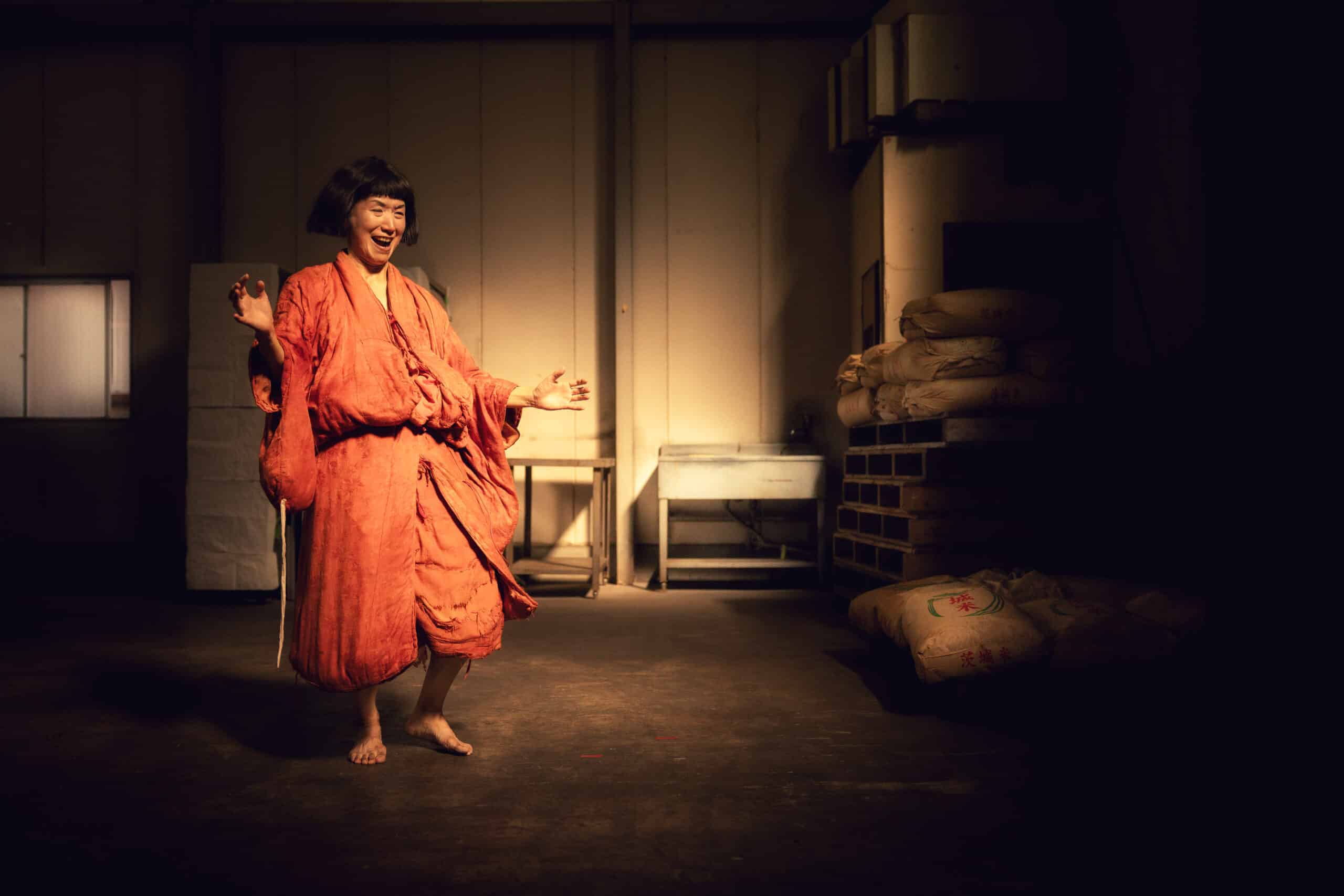

Pictured above and below is Butoh master Sanae Kagaya. Lucas met and photographed her after the initial workshop with Torifune Butoh Company.

The origin of Butoh is often traced to a 1959 performance by Tatsumi Hijikata. In this original 15-minute performance, it is said that a large portion of the audience left before it finished. It was rooted in post-war Japanese art, and was a form in response to other post-war styles. Butoh was subversive, rebellious, and even today as Lucas described, it can seem absurd and be shocking to watch. For more information on Butoh, see the links at the bottom of the article.

Bunraku

The second stop in Japan was at the south of the archipelago in Tokushima. Lucas visited with artist practitioners of Bunraku Puppetry and witnessed a performance of their company Tokushima Prefectural Awa Jurobe Yashiki. In this Bunraku performance, three puppeteers manipulated a single puppet. Lucas admired the synchronicity between the puppeteers and reflected that in this instance too, the art form seems familiar. He observed the same interconnectivity between the collaborating artists operating the puppet that we see in our ensembles in Dragone creations.

The performance Lucas attended was at eleven o’clock on a Monday morning. In a stroke of luck, he was the only audience member in attendance, so he could fully absorb the material and reflect on the experience. The theatre, a 300-year-old completely wooden structure was simple and pure. The artists were in their 60s and 70s and had all dedicated their lives to performing, preserving, and passing on this theatrical form.

Lucas explained his realization that what he’s looking for, the universal “gods of theatre” that connect international forms of human performance across mediums, traditions, and continents, is something beyond folkloric tradition. It’s a lifelong dedication to an art form. Lucas elaborated explaining that these forms require years of practice and sometimes only exist in the living bodies of the performers passed on from prior generations. This impermanence is something that drives his mission to understand, capture, and share these artists and forms with the world.

Unlike Butoh, Bunraku is hundreds of years old. It isn’t historically controversial or subversive in nature, but rather a traditional form of Japanese performance with origins in the seventeenth century. For more info see the links at the bottom of the page.

Kagura

The final stop in Japan was a 5-hour drive into nature, surrounded by mountains and trees. In a small village, Lucas witnessed a group of artists perform Kagura, a traditional form of dance theatre tied to religious ritual and traditionally performed for the gods. Lucas noted that while the performance he witnessed was audience facing, traditional Kagura performance can often take place in front of a temple, with the performers’ backs facing the audience as they deliver their presentation directly to the divine housed within.

Lucas explained that while Kagura is a very old form, it’s a “generous” form, allowing contemporary updates like smoke machines and effects. This is different than other popular forms of traditional Japanese performance like Noh theatre, that is understood to be rigid and exclusive in its adherence to traditional techniques. Similarly, Kagura allows more variation in masks than Noh theatre and provides room within the form to tell contemporary stories.

After witnessing the Kagura dancers and artists perform their craft, Lucas was struck by the similarity in approach they share with Dragone. They offer a mixture of tradition and innovation wrapped in artisanal human performance. The work is rich in context, skill, dedication, and humanity in exactly the way we strive for Dragone creations to be.

Additional Information

Butoh:

Torifune Butoh Company

https://www.torifune-butoh-sha.com/About

Google Arts and Culture

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/RQVBF_sJHCrpLw

Bunraku:

Tokushima Prefectural Awa Jurobe Yashiki

The History of Bunraku

Kagura:

Shamanic Dance in Japan: The Choreography of Possession in Kagura Performance

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1178756?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents